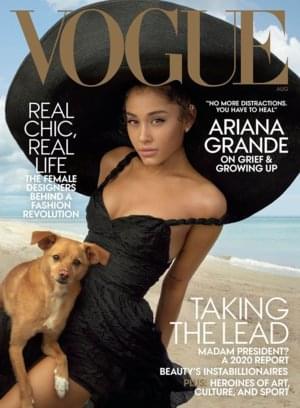

Ariana Grande on Grief and Growing Up Vogue (Ft. Ariana Grande)

На этой странице вы найдете полный текст песни "Ariana Grande on Grief and Growing Up" от Vogue (Ft. Ariana Grande). Lyrxo предлагает вам самый полный и точный текст этой композиции без лишних отвлекающих факторов. Узнайте все куплеты и припев, чтобы лучше понять любимую песню и насладиться ею в полной мере. Идеально для фанатов и всех, кто ценит качественную музыку.

IN FEBRUARY OF THIS YEAR, Ariana Grande had the number-one, number-two, and number-three songs in America. So extreme a choke hold of the Billboard charts had only one antecedent: the Beatles achieved it in 1964, when “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Twist and Shout,” and “Do You Want to Know a Secret” blanketed the airwaves. (Grande responded to the news of her pop preeminence in trademark terse, unpunctuated Twitterese: “wait what”.) But the singer, whose fame does not so much polarize as it sorts—into those who adore her, ape her high ponytail, and have made her the second-most-followed person on Instagram, behind the Portuguese soccer star Cristiano Ronaldo, and those for whom she barely registers (yet)—was in quiet knots. Thank U, Next, the album she wrote and recorded in a two-week fever dream the previous October, contained the most wrenchingly personal songs in her canon, and she was about to embark on a tour of at least 40 cities, where night after night she had to sing her way through a succession of private horrors.

“I was researching healing and PTSD and talking to therapists, and everyone was like, ‘You need a routine, a schedule,’ ” Grande says, yanking off a pair of black, ultra-high platform ankle boots so that she can crisscross her legs on the sofa and sit close. The boots, by the way, are Sergio Rossi, though we have to dig into the insole to determine this; Grande knows about music, she says, and not about clothes. “Of course because I’m an extremist, I’m like, OK, I’ll go on tour! But it’s hard to sing songs that are about wounds that are so fresh. It’s fun, it’s pop music, and I’m not trying to make it sound like anything that it’s not, but these songs to me really do represent some heavy shit.”

We are sitting in the home studio of Tommy Brown, Grande’s close friend and a producer on Thank U, Next, at the end of a noiseless cul-de-sac in Northridge, in the San Fernando Valley. (The earthquake that occurred here in 1994, six months after Grande’s birth, was among the strongest ever recorded in an American city.) A layer of cloud casts a dull light over the low-lying suburban houses and their front yards dotted with iceberg roses and pepper trees. Grande’s fans, known as Arianators, rivaling the Beyhive and the Little Monsters as the most dedicated and attuned in music, know that she loves the dour weather, hates the beach of her cosseted Floridian youth. “I’m like, please bring me the cold and the clammy and the clouds,” she says. “You want what you didn’t grow up getting.”

Although she has a home of her own in Beverly Hills, the kind of vast, marble-paved manse that young stars buy before they’re ready for them, Tommy’s is where she likes spending time when she’s in Los Angeles. Grande is wearing black leggings and an oversize sweatshirt emblazoned with the words SOCIAL HOUSE, the name of a pop duo from Pittsburgh who are friends and now one of her opening acts. A large white pearl, her birthstone, glimmers on her finger. (She is a Cancer: a little crab happiest in her shell.) It occurs to me that we’re talking about the weather for precisely the reason that people talk about the weather, in order to dance around the “heavy shit.” It’s a dance that spins out quickly. Grande begins to cry nine minutes into our conversation, at the mention of Coachella, which she headlined this year for the first time. Following a bumbling interchange of apologies—“I’m so sorry I’m crying,” “I’m so sorry I made you cry”—she explains that the festival offered near-constant reminders of the rapper Mac Miller (born Malcolm McCormick), her dear friend, collaborator, and ex-boyfriend, who died of an accidental overdose in September 2018. I imagined we would visit this and other delicate topics somewhere deep in our discussion, but grief creates a conversational black hole, drawing all particles to it. “I never thought I’d even go to Coachella,” she explains. “I was always a person who never went to festivals and never went out and had fun like that. But the first time I went was to see Malcolm perform, and it was such an incredible experience. I went the second year as well, and I associate...heavily...it was just kind of a mindfuck, processing how much has happened in such a brief period.”

For a woman who recently turned 26 and is enjoying the most successful chapter of her career, it has also been a spectacularly, and publicly, brutal couple of years. Fifteen months before Miller’s death, in May 2017, Grande had just finished the encore of a sold-out show on her Dangerous Woman tour in Manchester, England, when a suicide bomber detonated in the foyer, leaving 23 people dead, including an eight-year-old concertgoer. Shell-shocked and reeling, Grande and her mother, who was in the audience that night, flew home to Florida. (The tweet she mustered the next day was for a time the most-liked in the medium’s history: “broken. from the bottom of my heart, i am so so sorry. i don’t have words.”) But she quickly determined that before she was going to sing anywhere again, she needed to sing in Manchester. She returned two weeks later to visit survivors in hospitals and families in mourning. And she staged a benefit concert that raised $25 million. Guest stars included Coldplay, Katy Perry, and Justin Bieber, and Grande cruised the stage belting out her dirtiest songs at the request of one victim’s mother after it was suggested that the bomber, who had links to the Islamic State, had acted in protest of her racy pop persona.

But it was Grande’s culminating rendition of “Over the Rainbow,” intoned through her sobs, that is the night’s eternal image. If you didn’t know Ari, as her friends call her, if you sorted into that other group and assumed that Grande was a lab-engineered Frankensinger, a sexy cyborg extruding melismas in baby doll dresses and kitten ears, here may have been the first piece of evidence to the contrary. “Ariana’s an open book,” says her friend Miley Cyrus, who flew over for the concert. “She has always shared her experiences with this beautiful blend of reality and the fantasy that pop culture requires. But holding her in my arms that night and feeling her shake from the loss of lives, literally feeling her heart pounding against mine—when you can let down the personas and cry with the rest of the world, it’s unifying. It’s a reminder that music can be our greatest healer.”

She released no original music until the following spring, when “No Tears Left to Cry,” the first single off her fourth studio album, Sweetener, offered up a dance-floor hymn to optimism in the face of catastrophe. (The album’s closing track, “Get Well Soon,” addresses Manchester’s survivors directly. Including a period of silence at the song’s end, it clocks in at 5:22, the date of the bombing.) But in November 2018, after Miller’s death and the dissolution of her brief engagement to the Saturday Night Live comic Pete Davidson, Grande had to acknowledge that she was far from cried out, and she did so in a now-famous tweet: “remember when i was like hey i have no tears left to cry and the universe was like HAAAAAAAAA bitch u thought.”

These words, classic darkly humorous and self-deprecating Grande, are about as far as she has been willing to go toward addressing the events of the last two years. “I’ve been open in my art and open in my DMs and my conversations with my fans directly, and I want to be there for them, so I share things that I think they’ll find comfort in knowing that I go through as well,” she explains. “But also there are a lot of things that I swallow on a daily basis that I don’t want to share with them, because they’re mine. But they know that. They can literally see it in my eyes. They know when I’m disconnected, when I’m happy, when I’m tired. It’s this weird thing we have. We’re like fucking E.T. and Elliott.” Grande admits to approaching our conversation with a mix of dread and guilt about her dread. “I’m a person who’s been through a lot and doesn’t know what to say about any of it to myself, let alone the world. I see myself onstage as this perfectly polished, great-at-my-job entertainer, and then in situations like this I’m just this little basket-case puddle of figuring it out.” She laughs through her sniffles. “I have to be the luckiest girl in the world, and the unluckiest, for sure. I’m walking this fine line between healing myself and not letting the things that I’ve gone through be picked at before I’m ready, and also celebrating the beautiful things that have happened in my life and not feeling scared that they’ll be taken away from me because trauma tells me that they will be, you know what I mean?”

GRANDE GREW UP IN Boca Raton, Florida, in a gated community of expensive and lushly planted Mediterranean-style homes. Her mother, Joan Grande, Brooklyn-born and Barnard-educated, owns a business selling marine communications equipment; her father, Edward Butera, is a graphic designer. The couple divorced when Grande was eight. Ariana grew up in character, in a household that relished characters. The theme of her third birthday party was Jaws. She loved to run around the house in a Jason mask, and at Halloween, Joan liked to buy animal organs and leave them floating in dishes. “My family is eccentric and weird and loud and Italian,” Grande says. “There was always this fascination with the macabre. My mom is goth. Her whole wardrobe is modeled after Cersei Lannister’s. I’m not kidding. I’m like, ‘Mom, why are you wearing epaulets? It’s Thanksgiving.’ ”

Grande declared herself early. Joan recalls a car ride when Ariana was around three and a half; NSYNC was playing, and over and over the little girl perfectly matched JC Chasez’s high notes. There was a karaoke machine at home, and everyone—Ariana, her older half-brother, Frankie, and her mother—was always singing. “The soundtrack was Whitney, Madonna, Mariah, Celine, Barbra,” she recalls. “All the divas. Gay, divas, divas, gay, belting divas.” Joan also played a lot of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, and the family watched old musicals, especially the Judy Garland–Mickey Rooney pictures. “She was so intrigued by how pristine and precise these women were,” Joan recalls. “She studied them carefully.” When the family loved a show, they could be obsessive; Joan estimates that they saw Jersey Boys on Broadway close to 60 times.

Grande has a preternatural gift for impersonating other singers and actresses—a talent that has made her a surprise darling of the nighttime-television circuit. (After watching her host Saturday Night Live three years ago, Steven Spielberg texted Lorne Michaels to sing her praises.) Grande credits her healthy vocal technique to having learned to mimic Celine Dion, in particular, whose seamless blending through her registers and careful vocal placement have given her greater durability than many of her peers. “I learned how to make it sound like I was belting and being loud without actually belting and being loud,” Grande explains. “The voice is expensive, and if you’re spending it properly, you’ll be able to keep spending it.” When I tell her that I’m surprised by her interest in Judy Garland—not an obvious source of inspiration for a pop artist born nearly 25 years after her death—she cradles her arms in a manner that immediately brings the legend to mind. “I would stand in front of the TV and mimic her body movements. I was always fascinated. She carried herself in a way that was so protected and soft and Judy.”

After years of local children’s theater, Grande landed a role in the Broadway musical 13. (She was 14 at the time.) Weeks after the musical closed, she was cast as the goofy sidekick Cat Valentine on the Nickelodeon show Victorious, which made her a star with the tween set. “I never really saw myself as an actress,” she says, “but when I started talking about wanting to make R&B music at 14, they were like, ‘What the fuck would you sing about? This is never going to work. You should audition for some TV shows and build yourself a platform and get yourself out there, because you’re funny and cute and you should do that until you’re old enough to make the music you want to make.’ So I did that. I booked that TV show, and then I was like, OK, now can I make music?” While Victorious marched on, in her free time Grande liked to upload YouTube videos of herself singing covers of Adele, Whitney Houston, and Mariah Carey. It was a virtuoso rendition of Carey’s “Emotions,” which Grande posted in August 2012, when she was 19, that made her a hot property. Since then she has worked at a frantic pace, turning out five albums in six years, all of them certified platinum, and touring the world three times.

If one aspect of Grande’s career has been immune to critique, it’s her singing. Patti LaBelle came to know her several years ago, when Grande asked the R&B icon to perform at her birthday party. They have become friends. “She’s surpassed her peers,” LaBelle says. “And she does everything herself, which is not always the way with the young baby girls. She doesn’t need any machines. She’s a baby who’s able to sing like an older black woman.” LaBelle, whose four-year-old granddaughter, Gia, wears an Ariana ponytail, recalls the time when both singers performed for the Obamas at the Women of Soul concert at the White House. Grande was extremely nervous. “I said, ‘Girl, you’re a beast. Go up there and sing like that white-black woman you are.’ Ariana can sing me under the table—and listen, I can sing.”

“I was researching healing and PTSD and talking to therapists, and everyone was like, ‘You need a routine, a schedule,’ ” Grande says, yanking off a pair of black, ultra-high platform ankle boots so that she can crisscross her legs on the sofa and sit close. The boots, by the way, are Sergio Rossi, though we have to dig into the insole to determine this; Grande knows about music, she says, and not about clothes. “Of course because I’m an extremist, I’m like, OK, I’ll go on tour! But it’s hard to sing songs that are about wounds that are so fresh. It’s fun, it’s pop music, and I’m not trying to make it sound like anything that it’s not, but these songs to me really do represent some heavy shit.”

We are sitting in the home studio of Tommy Brown, Grande’s close friend and a producer on Thank U, Next, at the end of a noiseless cul-de-sac in Northridge, in the San Fernando Valley. (The earthquake that occurred here in 1994, six months after Grande’s birth, was among the strongest ever recorded in an American city.) A layer of cloud casts a dull light over the low-lying suburban houses and their front yards dotted with iceberg roses and pepper trees. Grande’s fans, known as Arianators, rivaling the Beyhive and the Little Monsters as the most dedicated and attuned in music, know that she loves the dour weather, hates the beach of her cosseted Floridian youth. “I’m like, please bring me the cold and the clammy and the clouds,” she says. “You want what you didn’t grow up getting.”

Although she has a home of her own in Beverly Hills, the kind of vast, marble-paved manse that young stars buy before they’re ready for them, Tommy’s is where she likes spending time when she’s in Los Angeles. Grande is wearing black leggings and an oversize sweatshirt emblazoned with the words SOCIAL HOUSE, the name of a pop duo from Pittsburgh who are friends and now one of her opening acts. A large white pearl, her birthstone, glimmers on her finger. (She is a Cancer: a little crab happiest in her shell.) It occurs to me that we’re talking about the weather for precisely the reason that people talk about the weather, in order to dance around the “heavy shit.” It’s a dance that spins out quickly. Grande begins to cry nine minutes into our conversation, at the mention of Coachella, which she headlined this year for the first time. Following a bumbling interchange of apologies—“I’m so sorry I’m crying,” “I’m so sorry I made you cry”—she explains that the festival offered near-constant reminders of the rapper Mac Miller (born Malcolm McCormick), her dear friend, collaborator, and ex-boyfriend, who died of an accidental overdose in September 2018. I imagined we would visit this and other delicate topics somewhere deep in our discussion, but grief creates a conversational black hole, drawing all particles to it. “I never thought I’d even go to Coachella,” she explains. “I was always a person who never went to festivals and never went out and had fun like that. But the first time I went was to see Malcolm perform, and it was such an incredible experience. I went the second year as well, and I associate...heavily...it was just kind of a mindfuck, processing how much has happened in such a brief period.”

For a woman who recently turned 26 and is enjoying the most successful chapter of her career, it has also been a spectacularly, and publicly, brutal couple of years. Fifteen months before Miller’s death, in May 2017, Grande had just finished the encore of a sold-out show on her Dangerous Woman tour in Manchester, England, when a suicide bomber detonated in the foyer, leaving 23 people dead, including an eight-year-old concertgoer. Shell-shocked and reeling, Grande and her mother, who was in the audience that night, flew home to Florida. (The tweet she mustered the next day was for a time the most-liked in the medium’s history: “broken. from the bottom of my heart, i am so so sorry. i don’t have words.”) But she quickly determined that before she was going to sing anywhere again, she needed to sing in Manchester. She returned two weeks later to visit survivors in hospitals and families in mourning. And she staged a benefit concert that raised $25 million. Guest stars included Coldplay, Katy Perry, and Justin Bieber, and Grande cruised the stage belting out her dirtiest songs at the request of one victim’s mother after it was suggested that the bomber, who had links to the Islamic State, had acted in protest of her racy pop persona.

But it was Grande’s culminating rendition of “Over the Rainbow,” intoned through her sobs, that is the night’s eternal image. If you didn’t know Ari, as her friends call her, if you sorted into that other group and assumed that Grande was a lab-engineered Frankensinger, a sexy cyborg extruding melismas in baby doll dresses and kitten ears, here may have been the first piece of evidence to the contrary. “Ariana’s an open book,” says her friend Miley Cyrus, who flew over for the concert. “She has always shared her experiences with this beautiful blend of reality and the fantasy that pop culture requires. But holding her in my arms that night and feeling her shake from the loss of lives, literally feeling her heart pounding against mine—when you can let down the personas and cry with the rest of the world, it’s unifying. It’s a reminder that music can be our greatest healer.”

She released no original music until the following spring, when “No Tears Left to Cry,” the first single off her fourth studio album, Sweetener, offered up a dance-floor hymn to optimism in the face of catastrophe. (The album’s closing track, “Get Well Soon,” addresses Manchester’s survivors directly. Including a period of silence at the song’s end, it clocks in at 5:22, the date of the bombing.) But in November 2018, after Miller’s death and the dissolution of her brief engagement to the Saturday Night Live comic Pete Davidson, Grande had to acknowledge that she was far from cried out, and she did so in a now-famous tweet: “remember when i was like hey i have no tears left to cry and the universe was like HAAAAAAAAA bitch u thought.”

These words, classic darkly humorous and self-deprecating Grande, are about as far as she has been willing to go toward addressing the events of the last two years. “I’ve been open in my art and open in my DMs and my conversations with my fans directly, and I want to be there for them, so I share things that I think they’ll find comfort in knowing that I go through as well,” she explains. “But also there are a lot of things that I swallow on a daily basis that I don’t want to share with them, because they’re mine. But they know that. They can literally see it in my eyes. They know when I’m disconnected, when I’m happy, when I’m tired. It’s this weird thing we have. We’re like fucking E.T. and Elliott.” Grande admits to approaching our conversation with a mix of dread and guilt about her dread. “I’m a person who’s been through a lot and doesn’t know what to say about any of it to myself, let alone the world. I see myself onstage as this perfectly polished, great-at-my-job entertainer, and then in situations like this I’m just this little basket-case puddle of figuring it out.” She laughs through her sniffles. “I have to be the luckiest girl in the world, and the unluckiest, for sure. I’m walking this fine line between healing myself and not letting the things that I’ve gone through be picked at before I’m ready, and also celebrating the beautiful things that have happened in my life and not feeling scared that they’ll be taken away from me because trauma tells me that they will be, you know what I mean?”

GRANDE GREW UP IN Boca Raton, Florida, in a gated community of expensive and lushly planted Mediterranean-style homes. Her mother, Joan Grande, Brooklyn-born and Barnard-educated, owns a business selling marine communications equipment; her father, Edward Butera, is a graphic designer. The couple divorced when Grande was eight. Ariana grew up in character, in a household that relished characters. The theme of her third birthday party was Jaws. She loved to run around the house in a Jason mask, and at Halloween, Joan liked to buy animal organs and leave them floating in dishes. “My family is eccentric and weird and loud and Italian,” Grande says. “There was always this fascination with the macabre. My mom is goth. Her whole wardrobe is modeled after Cersei Lannister’s. I’m not kidding. I’m like, ‘Mom, why are you wearing epaulets? It’s Thanksgiving.’ ”

Grande declared herself early. Joan recalls a car ride when Ariana was around three and a half; NSYNC was playing, and over and over the little girl perfectly matched JC Chasez’s high notes. There was a karaoke machine at home, and everyone—Ariana, her older half-brother, Frankie, and her mother—was always singing. “The soundtrack was Whitney, Madonna, Mariah, Celine, Barbra,” she recalls. “All the divas. Gay, divas, divas, gay, belting divas.” Joan also played a lot of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, and the family watched old musicals, especially the Judy Garland–Mickey Rooney pictures. “She was so intrigued by how pristine and precise these women were,” Joan recalls. “She studied them carefully.” When the family loved a show, they could be obsessive; Joan estimates that they saw Jersey Boys on Broadway close to 60 times.

Grande has a preternatural gift for impersonating other singers and actresses—a talent that has made her a surprise darling of the nighttime-television circuit. (After watching her host Saturday Night Live three years ago, Steven Spielberg texted Lorne Michaels to sing her praises.) Grande credits her healthy vocal technique to having learned to mimic Celine Dion, in particular, whose seamless blending through her registers and careful vocal placement have given her greater durability than many of her peers. “I learned how to make it sound like I was belting and being loud without actually belting and being loud,” Grande explains. “The voice is expensive, and if you’re spending it properly, you’ll be able to keep spending it.” When I tell her that I’m surprised by her interest in Judy Garland—not an obvious source of inspiration for a pop artist born nearly 25 years after her death—she cradles her arms in a manner that immediately brings the legend to mind. “I would stand in front of the TV and mimic her body movements. I was always fascinated. She carried herself in a way that was so protected and soft and Judy.”

After years of local children’s theater, Grande landed a role in the Broadway musical 13. (She was 14 at the time.) Weeks after the musical closed, she was cast as the goofy sidekick Cat Valentine on the Nickelodeon show Victorious, which made her a star with the tween set. “I never really saw myself as an actress,” she says, “but when I started talking about wanting to make R&B music at 14, they were like, ‘What the fuck would you sing about? This is never going to work. You should audition for some TV shows and build yourself a platform and get yourself out there, because you’re funny and cute and you should do that until you’re old enough to make the music you want to make.’ So I did that. I booked that TV show, and then I was like, OK, now can I make music?” While Victorious marched on, in her free time Grande liked to upload YouTube videos of herself singing covers of Adele, Whitney Houston, and Mariah Carey. It was a virtuoso rendition of Carey’s “Emotions,” which Grande posted in August 2012, when she was 19, that made her a hot property. Since then she has worked at a frantic pace, turning out five albums in six years, all of them certified platinum, and touring the world three times.

If one aspect of Grande’s career has been immune to critique, it’s her singing. Patti LaBelle came to know her several years ago, when Grande asked the R&B icon to perform at her birthday party. They have become friends. “She’s surpassed her peers,” LaBelle says. “And she does everything herself, which is not always the way with the young baby girls. She doesn’t need any machines. She’s a baby who’s able to sing like an older black woman.” LaBelle, whose four-year-old granddaughter, Gia, wears an Ariana ponytail, recalls the time when both singers performed for the Obamas at the Women of Soul concert at the White House. Grande was extremely nervous. “I said, ‘Girl, you’re a beast. Go up there and sing like that white-black woman you are.’ Ariana can sing me under the table—and listen, I can sing.”

Комментарии (0)

Минимальная длина комментария — 50 символов.