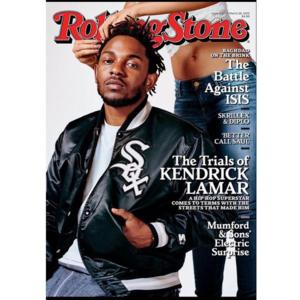

The Trials of Kendrick Lamar Rolling Stone (Ft. Kendrick Lamar)

На этой странице вы найдете полный текст песни "The Trials of Kendrick Lamar" от Rolling Stone (Ft. Kendrick Lamar). Lyrxo предлагает вам самый полный и точный текст этой композиции без лишних отвлекающих факторов. Узнайте все куплеты и припев, чтобы лучше понять любимую песню и насладиться ею в полной мере. Идеально для фанатов и всех, кто ценит качественную музыку.

A drizzly Sunday morning in Compton, the sky an un-California-ish gray. Into the parking lot of a local hamburger stand pulls a chromed-out black Mercedes SUV, driven by 27-year-old Kendrick Lamar, arguably the most talented rapper of his generation. there are a half-dozen guys from the neighborhood waiting to meet him: L, Turtle, G-Weed. "I grew up with all these cats," Lamar says. He nods to Mingo, a Compton-born sweetheart who is roughly the size of the truck he arrived in: "I don't need to hire a bodyguard. Look how fucking big he is!" The burger joint, Tam's, sits at the corner of Rosecrans and Central, a famous local spot recently made infamous when Suge Knight allegedly ran over two men with his truck in the parking lot, killing one of them. "Homey died right here," G-Weed says, pointing to a dark spot on the asphalt. "That security camera caught everything. They're building a case."

Lamar grew up just six blocks from here, in a little blue three-bedroom house at 1612 137th St. Across the street is the Louisiana Fried Chicken where he used to get the three-piece meal with fries and lemonade; over there is the Rite Aid where he walked to buy milk for his little brothers. Tam's was another hangout. "This is where I seen my second murder, actually." he says. "Eight years old, walking home from McNair Elementary. Dude was in the drive-thru ordering his food, and homey ran up, boom boom - smoked him." He saw his first murder at age five, a teenage drug dealer gunned down outside Lamar's apartment building. "After that," he says, "you just get numb to it."

It's almost noon, but Lamar is just starting his day - having spent a late night in the studio scrambling to finish his new album, To Pimp a Butterfly, which has to be done in five days. He's dressed casually in a gray hoodie, maroon sweatpants, and white socks with black slides, but recognizable enough that an old lady in line decides to tease him while complaining about the heat inside. "Y'all need to put the air conditioner on," she calls to the manager. "Kendrick Lamar is here!"

Lamar may be a two-time Grammy winner with a platinum debut executive-produced by Dr. Dre, and with fans from Kanye West to Taylor Swift. But here at Tam's, he's also Kendrick Duckworth, Paula and Kenny's son. Inside, a middle-aged woman who just left church comes up and gives him a hug, and he buys lunch for a cart-toting lady he knows used to be a harmless crack addict. ("She used to chase us with sticks and stuff, he says.) Outside, an old man in a motorized wheelchair scoots over to introduce himself. He says he moved here in 1951, when Compton was still majority-white. "Back in the day, we had the baddest cars in L.A.," he says. "I just wanted you to know where you came from. It's a hell of a neighborhood."

On his breakthrough album, 2012's good kid, m.A.A.d City, Lamar made his name by chronicling this neighborhood, vividly evoking a specific place (this same stretch of Rosecrans) and a specific time (in the summer of 2004, between 10th and 11th grade). It was a concept album about adolescence, told with cinematic precision through the eyes of someone young enough to recall every detail (as in: "Me and my niggas four deep in a white Toyota/A quarter tank of gas, one pistol, one orange soda")

Lamar's parents moved here from Chicago in 1984, three years before Kendrick was born. His dad, Kenny Duckworth, was reportedly running with a South Side street gang called the Gangster Disciples, so his mom, Paula Oliver, issued an ultimatum. "She said, 'I can't fuck with you if you ain't trying to better yourself,'" Lamar recounts. "'We can't be in the streets forever.'" They stuffed their clothes in two black garbage bags and boarded a train to California with $500. "They were going to go to San Bernardino," Lamar says. "But my Auntie Tina was in Compton. She got 'em a hotel until they got on their feet, and my mom got a job at McDonald's." For the first couple of years, they slept in their car or motels, or in the park when it was hot enough. "Eventually, they saved enough money to get their first apartment, and that's when they had me."

Lamar has a lot of good memories of Compton as a kid: riding bikes, doing back flips off friends' roofs, sneaking into the living room during his parents' house parties. ("I'd catch him in the middle of the dance floor with his shirt off," his mom says. "Like, 'What the...? Get back in that room!'") Then there's one of his earliest memories - the afternoon of April 29th, 1992, the first day of the South Central riots

Kendrick was four. "I remember riding with my pops down Bullis Road, and looking out the window and seeing motherfuckers just running," he says. "I can see smoke. We stop, and my pops goes into the AutoZone and comes out rolling four tires. I know he didn't buy them. I'm like, 'What's going on?'" (Says Kenny, "We were all taking stuff. That's the way it was in the riots!")

"Then we get to the house," Lamar continues, "and him and my uncles are like, 'We fixing to get this, we fixing to get that, we fixing to get all this shit!' I'm thinking they're robbing. There's some real mayhem going on in L.A. Then, as time progresses, I'm watching the news, hearing about Rodney King and all this, I said to my mom, 'So the police beat up a black man, and now everybody's mad? Ok. I get it now.'"

We've been sitting on the patio a while when Lamar sees someone he knows at the bus stop. "Matt Jeezy! What up, bro?" Matt Jeezy nods. "That's my boy," Lamar says. "He's part of the inner circle." Lamar has a few friends like this, guys he's known all his life. But often he'd rather be by himself

"He was always a loner," Kendrick's mom says. Lamar agrees: "I was always in the corner of the room watching." He has two little brothers and one younger sister, but until he was seven, he was an only child. He was so precocious his parents nicknamed him Man-Man. "I grew up fast as fuck," he says. "My moms used to walk me home from school - we didn't have no car - and we'd talk from the county building to the welfare office." "He would ask me questions about Section 8 and the Housing Authority, so I'd explain it to him," his mom says. "I was keeping it real."

The Duckworths survived on welfare and food stamps, and Paula did hair for $20 a head. His dad had a job at KFC, but at a certain point, says Lamar, "I realized his work schedule wasn't really adding up." It wasn't until later that he suspected Kenny was probably making money off the streets. "They wanted to keep me innocent," Lamar says now. "I love them for that." To this day, he and his dad have never discussed it. "I don't know what type of demons he has," Lamar says, "but I don't wanna bring them shits up." (Says Kenny, "I don't want to talk about that bad time. But I did what I had to do.")

There's a famous story from Tom Petty's childhood in which a 10-year-old Tom sees Elvis shooting a movie near his hometown in Florida, takes on look at the white Cadillac and the girls, and decides to become a rock star on the spot. Lamar has a similar story - only for him it's sitting on his dad's shoulders outside the Compton Swap Meet, age eight, watching Dr. Dre and 2Pac shoot a video for "California Love." "I want to say they were in a white Bentley," Lamar says. (It was actually black.) "These motorcycle cops trying to conduct traffic but one almost scraped the car, and Pac stood up on the passenger seat, like, 'Yo, what the fuck!'" He laughs. "Yelling at the police, just like on his motherfucking songs. He gave us what we wanted."

Lamar grew up just six blocks from here, in a little blue three-bedroom house at 1612 137th St. Across the street is the Louisiana Fried Chicken where he used to get the three-piece meal with fries and lemonade; over there is the Rite Aid where he walked to buy milk for his little brothers. Tam's was another hangout. "This is where I seen my second murder, actually." he says. "Eight years old, walking home from McNair Elementary. Dude was in the drive-thru ordering his food, and homey ran up, boom boom - smoked him." He saw his first murder at age five, a teenage drug dealer gunned down outside Lamar's apartment building. "After that," he says, "you just get numb to it."

It's almost noon, but Lamar is just starting his day - having spent a late night in the studio scrambling to finish his new album, To Pimp a Butterfly, which has to be done in five days. He's dressed casually in a gray hoodie, maroon sweatpants, and white socks with black slides, but recognizable enough that an old lady in line decides to tease him while complaining about the heat inside. "Y'all need to put the air conditioner on," she calls to the manager. "Kendrick Lamar is here!"

Lamar may be a two-time Grammy winner with a platinum debut executive-produced by Dr. Dre, and with fans from Kanye West to Taylor Swift. But here at Tam's, he's also Kendrick Duckworth, Paula and Kenny's son. Inside, a middle-aged woman who just left church comes up and gives him a hug, and he buys lunch for a cart-toting lady he knows used to be a harmless crack addict. ("She used to chase us with sticks and stuff, he says.) Outside, an old man in a motorized wheelchair scoots over to introduce himself. He says he moved here in 1951, when Compton was still majority-white. "Back in the day, we had the baddest cars in L.A.," he says. "I just wanted you to know where you came from. It's a hell of a neighborhood."

On his breakthrough album, 2012's good kid, m.A.A.d City, Lamar made his name by chronicling this neighborhood, vividly evoking a specific place (this same stretch of Rosecrans) and a specific time (in the summer of 2004, between 10th and 11th grade). It was a concept album about adolescence, told with cinematic precision through the eyes of someone young enough to recall every detail (as in: "Me and my niggas four deep in a white Toyota/A quarter tank of gas, one pistol, one orange soda")

Lamar's parents moved here from Chicago in 1984, three years before Kendrick was born. His dad, Kenny Duckworth, was reportedly running with a South Side street gang called the Gangster Disciples, so his mom, Paula Oliver, issued an ultimatum. "She said, 'I can't fuck with you if you ain't trying to better yourself,'" Lamar recounts. "'We can't be in the streets forever.'" They stuffed their clothes in two black garbage bags and boarded a train to California with $500. "They were going to go to San Bernardino," Lamar says. "But my Auntie Tina was in Compton. She got 'em a hotel until they got on their feet, and my mom got a job at McDonald's." For the first couple of years, they slept in their car or motels, or in the park when it was hot enough. "Eventually, they saved enough money to get their first apartment, and that's when they had me."

Lamar has a lot of good memories of Compton as a kid: riding bikes, doing back flips off friends' roofs, sneaking into the living room during his parents' house parties. ("I'd catch him in the middle of the dance floor with his shirt off," his mom says. "Like, 'What the...? Get back in that room!'") Then there's one of his earliest memories - the afternoon of April 29th, 1992, the first day of the South Central riots

Kendrick was four. "I remember riding with my pops down Bullis Road, and looking out the window and seeing motherfuckers just running," he says. "I can see smoke. We stop, and my pops goes into the AutoZone and comes out rolling four tires. I know he didn't buy them. I'm like, 'What's going on?'" (Says Kenny, "We were all taking stuff. That's the way it was in the riots!")

"Then we get to the house," Lamar continues, "and him and my uncles are like, 'We fixing to get this, we fixing to get that, we fixing to get all this shit!' I'm thinking they're robbing. There's some real mayhem going on in L.A. Then, as time progresses, I'm watching the news, hearing about Rodney King and all this, I said to my mom, 'So the police beat up a black man, and now everybody's mad? Ok. I get it now.'"

We've been sitting on the patio a while when Lamar sees someone he knows at the bus stop. "Matt Jeezy! What up, bro?" Matt Jeezy nods. "That's my boy," Lamar says. "He's part of the inner circle." Lamar has a few friends like this, guys he's known all his life. But often he'd rather be by himself

"He was always a loner," Kendrick's mom says. Lamar agrees: "I was always in the corner of the room watching." He has two little brothers and one younger sister, but until he was seven, he was an only child. He was so precocious his parents nicknamed him Man-Man. "I grew up fast as fuck," he says. "My moms used to walk me home from school - we didn't have no car - and we'd talk from the county building to the welfare office." "He would ask me questions about Section 8 and the Housing Authority, so I'd explain it to him," his mom says. "I was keeping it real."

The Duckworths survived on welfare and food stamps, and Paula did hair for $20 a head. His dad had a job at KFC, but at a certain point, says Lamar, "I realized his work schedule wasn't really adding up." It wasn't until later that he suspected Kenny was probably making money off the streets. "They wanted to keep me innocent," Lamar says now. "I love them for that." To this day, he and his dad have never discussed it. "I don't know what type of demons he has," Lamar says, "but I don't wanna bring them shits up." (Says Kenny, "I don't want to talk about that bad time. But I did what I had to do.")

There's a famous story from Tom Petty's childhood in which a 10-year-old Tom sees Elvis shooting a movie near his hometown in Florida, takes on look at the white Cadillac and the girls, and decides to become a rock star on the spot. Lamar has a similar story - only for him it's sitting on his dad's shoulders outside the Compton Swap Meet, age eight, watching Dr. Dre and 2Pac shoot a video for "California Love." "I want to say they were in a white Bentley," Lamar says. (It was actually black.) "These motorcycle cops trying to conduct traffic but one almost scraped the car, and Pac stood up on the passenger seat, like, 'Yo, what the fuck!'" He laughs. "Yelling at the police, just like on his motherfucking songs. He gave us what we wanted."

Комментарии (0)

Минимальная длина комментария — 50 символов.