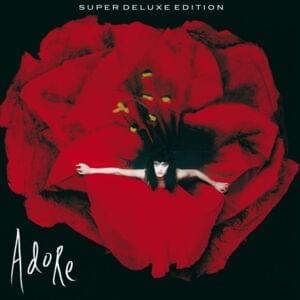

2014 Adore Reissue Liner Notes The Smashing Pumpkins

На этой странице вы найдете полный текст песни "2014 Adore Reissue Liner Notes" от The Smashing Pumpkins. Lyrxo предлагает вам самый полный и точный текст этой композиции без лишних отвлекающих факторов. Узнайте все куплеты и припев, чтобы лучше понять любимую песню и насладиться ею в полной мере. Идеально для фанатов и всех, кто ценит качественную музыку.

Part 1: 'Adore' of Perceptions

By David Wild

Adore is the surprisingly beautiful sound of a great band falling apart.

Just about a decade and a half ago-shortly after the release of The Smashing Pumpkins' Adore album met with an underwhelming commercial response-Billy Corgan told David Fricke of Rolling Stone, "At the end of the day, if people do not connect with Adore, that is my responsibility. But in fifteen years, if somebody pulls me over and says, 'Adore is the best record you ever did,' I'm going to fall over laughing."

Asked now about that comment--and about his current feelings regarding Adore today--Corgan laughs, though for the record, he does not fall over. "I love Adore," he explains, "but for a while my opinion of the record was so intertwined with people's reaction to it at the time. I would say that my kind of iffy feeling lingered long past the point when a lot of fans seemed to come back around to the record--which seemed to really start happening around seven years ago. Now Adore is name-checked by fans constantly."

The immediate reaction to Adore was complicated, just as its creation came in the aftermath of decidedly complicated times for Corgan. For years, The Smashing Pumpkins had just become bigger and bigger on a number of levels with each studio release: Gish in 1991, Siamese Dream in 1993, Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness in 1995. But Adore would ultimately reflect a significant change of pace and style. In addition to Jimmy Chamberlin having been fired from the band, Corgan had also gone through a divorce and the death of his mother. In this context, it seems unsurprising that Adore was heard as anything but just another Smashing Pumpkins album.

"It was this weird thing where for five or six years, every time that I opened my mouth, I seemed to follow it up with something bigger," Corgan says today. "It felt like being a guy on a roll of the dice, always rolling the right number or something. So this period was my first big misstep--at least that's how it was perceived at the time."

In fact, some critics praised the album, but the public seemed thrown by the significantly different, more intimate, and less guitar based sound of Adore, with its more quietly introspective and poetic mood and gorgeous touches of both folk and electronica. "I think I put more work into textural qualities of the record. Of course, it was lost in the onrush to condemn it."

When reminded that some critics actually seemed to like the album more than the public, Corgan explains, "I don't have that memory, but I was inside the bubble. I don't feel like I ever lost touch with reality; I just didn't know what to do about it."

In a variety of ways, the muted response to Adore struck Corgan as an almost inevitable moment of reckoning. "Success has a funny way of smoothing over relationships." He explains, "People tolerate you a little more than they would otherwise. There's this funny feeling that's sort of to your advantage, so you're not exactly fighting it, but there's still a feeling that something's not quite right either. And then there's some sort of moment of accountability for it or responsibility. Maybe it's a spiritual thing. Maybe it's just the law of energy. You can only run at a thousand miles an hour for so long. Those sorts of live events took me below a certain level of focus or energy or invulnerability, and I believe I tried on Adore to accurately document that. I believe I said at the time, that the album was just as much about Jimmy NOT being there. I really felt like in many ways, Jimmy was there."

So Jimmy Chamberlin was a presence even in his absence?

"Oh absolutely, it was like the ghost of Jimmy was in the room," Corgan explains. "Jimmy was my greatest confidant in terms of musical solidarity. And so I didn't have this guy to take a track and make it better because Jimmy can read my mind. Suddenly I'm dealing with different personalities and I don't have the same drive. Over time, I see it as being akin to the loss of my mom because I didn't really deal with it. And because I hadn't grown up with my mother, that loss hit me in a funny way because we hadn't had the relationship that I wanted."

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, Corgan originally envisioned taking a different approach to recording hat would become the Adore album. "I think what was so confusing for most people who worked on the album, including my bandmates, was that Adore from a production standpoint is sort of about disassociation and disintegration and disembodiment."

Originally, Corgan began work with producer Brad Wood who had received positive attention for his work with Liz Phair, among others, but eventually Corgan concluded that Wood's low-fi, indie approach did not mesh well with his during early sessions that saw the Pumpkins joined by drummer Matt Walker of Filter. "I originally had the crazy idea that we'd move studios each week," Corgan recalls. ""In Brad's defense, that put a pressure on him he didn't need. I think I maybe had been listening to the Basement Tapes too much. The idea was we were going to roll into the studio and create. Which I sort of did for the first eight weeks, technical issues aside. But the band didn't really participate that much in that process. I don't know why, but to me they didn't seem that interested. So when I made the decision to take the whole thing to L.A.--and I'm sure weather had something to do with that--they clocked in for a while, and then just started fading away. They didn't want to sit there watching me sit and tweak sampled drums all day, and they didn't get what I was doing and why I was doing it. At some point they stopped coming in all together."

By David Wild

Adore is the surprisingly beautiful sound of a great band falling apart.

Just about a decade and a half ago-shortly after the release of The Smashing Pumpkins' Adore album met with an underwhelming commercial response-Billy Corgan told David Fricke of Rolling Stone, "At the end of the day, if people do not connect with Adore, that is my responsibility. But in fifteen years, if somebody pulls me over and says, 'Adore is the best record you ever did,' I'm going to fall over laughing."

Asked now about that comment--and about his current feelings regarding Adore today--Corgan laughs, though for the record, he does not fall over. "I love Adore," he explains, "but for a while my opinion of the record was so intertwined with people's reaction to it at the time. I would say that my kind of iffy feeling lingered long past the point when a lot of fans seemed to come back around to the record--which seemed to really start happening around seven years ago. Now Adore is name-checked by fans constantly."

The immediate reaction to Adore was complicated, just as its creation came in the aftermath of decidedly complicated times for Corgan. For years, The Smashing Pumpkins had just become bigger and bigger on a number of levels with each studio release: Gish in 1991, Siamese Dream in 1993, Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness in 1995. But Adore would ultimately reflect a significant change of pace and style. In addition to Jimmy Chamberlin having been fired from the band, Corgan had also gone through a divorce and the death of his mother. In this context, it seems unsurprising that Adore was heard as anything but just another Smashing Pumpkins album.

"It was this weird thing where for five or six years, every time that I opened my mouth, I seemed to follow it up with something bigger," Corgan says today. "It felt like being a guy on a roll of the dice, always rolling the right number or something. So this period was my first big misstep--at least that's how it was perceived at the time."

In fact, some critics praised the album, but the public seemed thrown by the significantly different, more intimate, and less guitar based sound of Adore, with its more quietly introspective and poetic mood and gorgeous touches of both folk and electronica. "I think I put more work into textural qualities of the record. Of course, it was lost in the onrush to condemn it."

When reminded that some critics actually seemed to like the album more than the public, Corgan explains, "I don't have that memory, but I was inside the bubble. I don't feel like I ever lost touch with reality; I just didn't know what to do about it."

In a variety of ways, the muted response to Adore struck Corgan as an almost inevitable moment of reckoning. "Success has a funny way of smoothing over relationships." He explains, "People tolerate you a little more than they would otherwise. There's this funny feeling that's sort of to your advantage, so you're not exactly fighting it, but there's still a feeling that something's not quite right either. And then there's some sort of moment of accountability for it or responsibility. Maybe it's a spiritual thing. Maybe it's just the law of energy. You can only run at a thousand miles an hour for so long. Those sorts of live events took me below a certain level of focus or energy or invulnerability, and I believe I tried on Adore to accurately document that. I believe I said at the time, that the album was just as much about Jimmy NOT being there. I really felt like in many ways, Jimmy was there."

So Jimmy Chamberlin was a presence even in his absence?

"Oh absolutely, it was like the ghost of Jimmy was in the room," Corgan explains. "Jimmy was my greatest confidant in terms of musical solidarity. And so I didn't have this guy to take a track and make it better because Jimmy can read my mind. Suddenly I'm dealing with different personalities and I don't have the same drive. Over time, I see it as being akin to the loss of my mom because I didn't really deal with it. And because I hadn't grown up with my mother, that loss hit me in a funny way because we hadn't had the relationship that I wanted."

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, Corgan originally envisioned taking a different approach to recording hat would become the Adore album. "I think what was so confusing for most people who worked on the album, including my bandmates, was that Adore from a production standpoint is sort of about disassociation and disintegration and disembodiment."

Originally, Corgan began work with producer Brad Wood who had received positive attention for his work with Liz Phair, among others, but eventually Corgan concluded that Wood's low-fi, indie approach did not mesh well with his during early sessions that saw the Pumpkins joined by drummer Matt Walker of Filter. "I originally had the crazy idea that we'd move studios each week," Corgan recalls. ""In Brad's defense, that put a pressure on him he didn't need. I think I maybe had been listening to the Basement Tapes too much. The idea was we were going to roll into the studio and create. Which I sort of did for the first eight weeks, technical issues aside. But the band didn't really participate that much in that process. I don't know why, but to me they didn't seem that interested. So when I made the decision to take the whole thing to L.A.--and I'm sure weather had something to do with that--they clocked in for a while, and then just started fading away. They didn't want to sit there watching me sit and tweak sampled drums all day, and they didn't get what I was doing and why I was doing it. At some point they stopped coming in all together."

Комментарии (0)

Минимальная длина комментария — 50 символов.