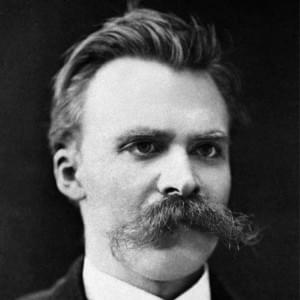

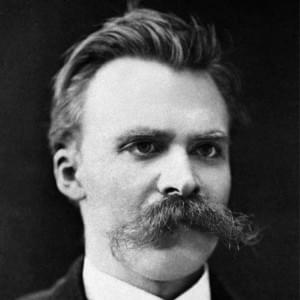

The Religious Life - 108-119 Friedrich Nietzsche

На этой странице вы найдете полный текст песни "The Religious Life - 108-119" от Friedrich Nietzsche. Lyrxo предлагает вам самый полный и точный текст этой композиции без лишних отвлекающих факторов. Узнайте все куплеты и припев, чтобы лучше понять любимую песню и насладиться ею в полной мере. Идеально для фанатов и всех, кто ценит качественную музыку.

108

The Double Contest Against Evil.—If an evil afflicts us we can either so deal with it as to remove its cause or else so deal with it that its effect upon our feeling is changed: hence look upon the evil as a benefit of which the uses will perhaps first become evident in some subsequent period. Religion and art (and also the metaphysical philosophy) strive to effect an alteration of the feeling, partly by an alteration of our judgment respecting the experience (for example, with the aid of the dictum "whom God loves, he chastizes") partly by the awakening of a joy in pain, in emotion especially (whence the art of tragedy had its origin). The more one is disposed to interpret away and justify, the less likely he is to look directly at the causes of evil and eliminate them. An instant alleviation and narcotizing of pain, as is usual in the case of tooth ache, is sufficient for him even in the severest suffering. The more the domination of religions and of all narcotic arts declines, the more searchingly do men look to the elimination[137] of evil itself, which is a rather bad thing for the tragic poets—for there is ever less and less material for tragedy, since the domain of unsparing, immutable destiny grows constantly more circumscribed—and a still worse thing for the priests, for these last have lived heretofore upon the narcoticizing of human ill.

109

Sorrow is Knowledge.—How willingly would not one exchange the false assertions of the homines religiosi that there is a god who commands us to be good, who is the sentinel and witness of every act, every moment, every thought, who loves us, who plans our welfare in every misfortune—how willingly would not one exchange these for truths as healing, beneficial and grateful as those delusions! But there are no such truths. Philosophy can at most set up in opposition to them other metaphysical plausibilities (fundamental untruths as well). The tragedy of it all is that, although one cannot believe these dogmas of religion and metaphysics if one adopts in heart and head the potent methods of truth, one has yet become, through human evolution, so tender, susceptible, sensitive, as to stand in need of the most effective means of rest and consolation. From this[138] state of things arises the danger that, through the perception of truth or, more accurately, seeing through delusion, one may bleed to death. Byron has put this into deathless verse:

"Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most

Must mourn the deepest o'er the fatal truth,

The tree of knowledge is not that of life."

Against such cares there is no better protective than the light fancy of Horace, (at any rate during the darkest hours and sun eclipses of the soul) expressed in the words

"quid aeternis minorem

consiliis animum fatigas?

cur non sub alta vel platano vel hac

pinu jacentes."22

22

Then wherefore should you, who are mortal, outwear

Your soul with a profitless burden of care

Say, why should we not, flung at ease neath this pine,

Or a plane-tree's broad umbrage, quaff gaily our wine?

(Translation of Sir Theodore Martin.)

At any rate, light fancy or heavy heartedness of any degree must be better than a romantic retrogression and desertion of one's flag, an approach to Christianity in any form: for with it, in the present state of knowledge, one can have nothing to do without hopelessly defiling one's intellectual integrity and surrendering it unconditionally. These woes may be painful enough, but without pain one cannot become a leader and guide of humanity: and woe to him who would be such and lacks this pure integrity of the intellect!

The Double Contest Against Evil.—If an evil afflicts us we can either so deal with it as to remove its cause or else so deal with it that its effect upon our feeling is changed: hence look upon the evil as a benefit of which the uses will perhaps first become evident in some subsequent period. Religion and art (and also the metaphysical philosophy) strive to effect an alteration of the feeling, partly by an alteration of our judgment respecting the experience (for example, with the aid of the dictum "whom God loves, he chastizes") partly by the awakening of a joy in pain, in emotion especially (whence the art of tragedy had its origin). The more one is disposed to interpret away and justify, the less likely he is to look directly at the causes of evil and eliminate them. An instant alleviation and narcotizing of pain, as is usual in the case of tooth ache, is sufficient for him even in the severest suffering. The more the domination of religions and of all narcotic arts declines, the more searchingly do men look to the elimination[137] of evil itself, which is a rather bad thing for the tragic poets—for there is ever less and less material for tragedy, since the domain of unsparing, immutable destiny grows constantly more circumscribed—and a still worse thing for the priests, for these last have lived heretofore upon the narcoticizing of human ill.

109

Sorrow is Knowledge.—How willingly would not one exchange the false assertions of the homines religiosi that there is a god who commands us to be good, who is the sentinel and witness of every act, every moment, every thought, who loves us, who plans our welfare in every misfortune—how willingly would not one exchange these for truths as healing, beneficial and grateful as those delusions! But there are no such truths. Philosophy can at most set up in opposition to them other metaphysical plausibilities (fundamental untruths as well). The tragedy of it all is that, although one cannot believe these dogmas of religion and metaphysics if one adopts in heart and head the potent methods of truth, one has yet become, through human evolution, so tender, susceptible, sensitive, as to stand in need of the most effective means of rest and consolation. From this[138] state of things arises the danger that, through the perception of truth or, more accurately, seeing through delusion, one may bleed to death. Byron has put this into deathless verse:

"Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most

Must mourn the deepest o'er the fatal truth,

The tree of knowledge is not that of life."

Against such cares there is no better protective than the light fancy of Horace, (at any rate during the darkest hours and sun eclipses of the soul) expressed in the words

"quid aeternis minorem

consiliis animum fatigas?

cur non sub alta vel platano vel hac

pinu jacentes."22

22

Then wherefore should you, who are mortal, outwear

Your soul with a profitless burden of care

Say, why should we not, flung at ease neath this pine,

Or a plane-tree's broad umbrage, quaff gaily our wine?

(Translation of Sir Theodore Martin.)

At any rate, light fancy or heavy heartedness of any degree must be better than a romantic retrogression and desertion of one's flag, an approach to Christianity in any form: for with it, in the present state of knowledge, one can have nothing to do without hopelessly defiling one's intellectual integrity and surrendering it unconditionally. These woes may be painful enough, but without pain one cannot become a leader and guide of humanity: and woe to him who would be such and lacks this pure integrity of the intellect!

Комментарии (0)

Минимальная длина комментария — 50 символов.