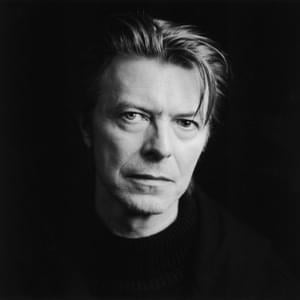

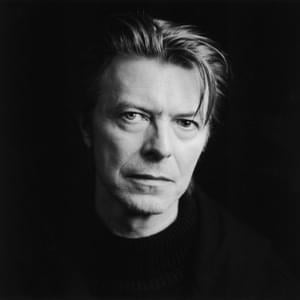

Riverside employment lawyers David Bowie

На этой странице вы найдете полный текст песни "Riverside employment lawyers" от David Bowie. Lyrxo предлагает вам самый полный и точный текст этой композиции без лишних отвлекающих факторов. Узнайте все куплеты и припев, чтобы лучше понять любимую песню и насладиться ею в полной мере. Идеально для фанатов и всех, кто ценит качественную музыку.

Plaintiff taxpayers appealed a judgment for defendant city, entered in the Superior Court of Los Angeles County (California), in their suits for a refund of taxes they paid pursuant to Los Angeles Business Tax Ordinance §§ 21.168.1, 21.190.

Plaintiff taxpayers manufactured and delivered military weapons, equipment, and supplies for the federal government. Some of their shipments were made on government bills of lading; others were made on commercial bills of lading. Plaintiffs reported the gross receipts from their government contracts to defendant city, but excluded the receipts attributable to property shipped outside the state by bills of lading. Defendant assessed tax deficiencies, Riverside employment lawyers plaintiffs paid. Plaintiffs then brought complaints for refunds. The court reversed the trial court's order in favor of defendant. Plaintiffs were taxable on their gross receipts under Los Angeles Business Tax Ordinance §§ 21.166, 21.167, not under Los Angeles Business Tax Ordinance § 21.190, as defendant asserted; plaintiffs' processes of sale and service were commercially inseparable and could not be assessed separately. Plaintiffs were taxable on gross receipts for shipments on government bills of lading. These were not exempted by Los Angeles Business Tax Ordinance § 21.168.1, as were those shipments made on commercial bills of lading.

The court reversed the judgment for defendant city, holding that plaintiff taxpayers could be taxed on their gross receipts from government contracts but that they were not taxable under the higher rate of a catch-all ordinance provision. The court also held plaintiffs liable for gross receipts attributable to shipments to points outside the state on government bills of lading, but not on commercial bills of lading.

Plaintiff brought an action charging defendant and others with violating the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act (CUTSA), Civ. Code, § 3426, et seq., by misappropriating certain trade secrets belonging to plaintiff. The Superior Court of Santa Clara County, California, dismissed the complaint. Plaintiff petitioned for a writ of mandate directing the trial court to set aside its order of dismissal and to permit the matter to proceed to trial.

Not long after filing suit, plaintiff went through bankruptcy proceedings, selling its rights in the alleged trade secrets, while reserving its rights of action for misappropriation commencing before the date of the transfer. Despite the efforts by defendant's counsel to conjure up a "current ownership rule," the court found no support for such a rule in the text of the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act, Civ. Code, § 3426, et seq., cases applying it, or legislative history. Nor did the court find any evidence of such a rule in patent or copyright law, which defendants cited by analogy. Defendants offered no persuasive argument from policy for the court's adoption of such a rule. Although there might be situations where a suit by a former owner raised concerns about the rights of absent parties, or a risk of multiple or inconsistent liabilities on the part of parties before the court, the remedy for such concerns rested in California's liberal and highly flexible procedures for the permissive or compulsory joinder of parties. Because plaintiff's sale of the trade secrets was not an impediment to its maintenance of its action, the trial court erred by dismissing the complaint.

The court issued a peremptory writ of mandate directing the trial court to set aside its order dismissing plaintiff's claims, and to proceed with their adjudication in a manner consistent with the court's opinion.

Plaintiff taxpayers manufactured and delivered military weapons, equipment, and supplies for the federal government. Some of their shipments were made on government bills of lading; others were made on commercial bills of lading. Plaintiffs reported the gross receipts from their government contracts to defendant city, but excluded the receipts attributable to property shipped outside the state by bills of lading. Defendant assessed tax deficiencies, Riverside employment lawyers plaintiffs paid. Plaintiffs then brought complaints for refunds. The court reversed the trial court's order in favor of defendant. Plaintiffs were taxable on their gross receipts under Los Angeles Business Tax Ordinance §§ 21.166, 21.167, not under Los Angeles Business Tax Ordinance § 21.190, as defendant asserted; plaintiffs' processes of sale and service were commercially inseparable and could not be assessed separately. Plaintiffs were taxable on gross receipts for shipments on government bills of lading. These were not exempted by Los Angeles Business Tax Ordinance § 21.168.1, as were those shipments made on commercial bills of lading.

The court reversed the judgment for defendant city, holding that plaintiff taxpayers could be taxed on their gross receipts from government contracts but that they were not taxable under the higher rate of a catch-all ordinance provision. The court also held plaintiffs liable for gross receipts attributable to shipments to points outside the state on government bills of lading, but not on commercial bills of lading.

Plaintiff brought an action charging defendant and others with violating the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act (CUTSA), Civ. Code, § 3426, et seq., by misappropriating certain trade secrets belonging to plaintiff. The Superior Court of Santa Clara County, California, dismissed the complaint. Plaintiff petitioned for a writ of mandate directing the trial court to set aside its order of dismissal and to permit the matter to proceed to trial.

Not long after filing suit, plaintiff went through bankruptcy proceedings, selling its rights in the alleged trade secrets, while reserving its rights of action for misappropriation commencing before the date of the transfer. Despite the efforts by defendant's counsel to conjure up a "current ownership rule," the court found no support for such a rule in the text of the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act, Civ. Code, § 3426, et seq., cases applying it, or legislative history. Nor did the court find any evidence of such a rule in patent or copyright law, which defendants cited by analogy. Defendants offered no persuasive argument from policy for the court's adoption of such a rule. Although there might be situations where a suit by a former owner raised concerns about the rights of absent parties, or a risk of multiple or inconsistent liabilities on the part of parties before the court, the remedy for such concerns rested in California's liberal and highly flexible procedures for the permissive or compulsory joinder of parties. Because plaintiff's sale of the trade secrets was not an impediment to its maintenance of its action, the trial court erred by dismissing the complaint.

The court issued a peremptory writ of mandate directing the trial court to set aside its order dismissing plaintiff's claims, and to proceed with their adjudication in a manner consistent with the court's opinion.

Комментарии (0)

Минимальная длина комментария — 50 символов.