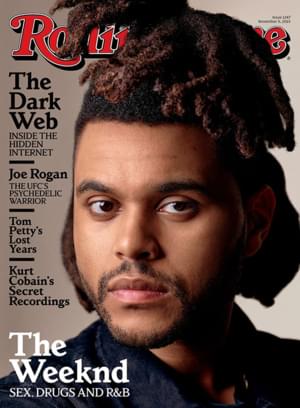

The Weeknd Rolling Stones Interview The Weeknd

На этой странице вы найдете полный текст песни "The Weeknd Rolling Stones Interview" от The Weeknd. Lyrxo предлагает вам самый полный и точный текст этой композиции без лишних отвлекающих факторов. Узнайте все куплеты и припев, чтобы лучше понять любимую песню и насладиться ею в полной мере. Идеально для фанатов и всех, кто ценит качественную музыку.

So is this swearing or no swearing?” In a darkened soundstage on the outskirts of London, Abel Tesfaye is wondering if he can say “fuck” or not. Tesfaye, better known as breakout pop sensation the Weeknd, is at a rehearsal for Later...With Jools Holland, the BBC music show, about to soundcheck his smash hit “The Hills,” a four-minute horror-movie booty call featuring more than a dozen f-bombs. For Tesfaye, that’s relatively clean, but he knows the pensioners in Twickenham might disagree. So when the verdict comes back “no swearing,” he nods and smoothly pivots to a censored version — a small gesture that says a lot about the kind of professional he has become.

“The Hills” is currently enjoying its fourth straight week at Number One, a feat made even more impressive because it took the place of another Weeknd track, “Can’t Feel My Face” — Spotify’s official song of the summer, and the only song about cocaine ever to be lip-synced by Tom Cruise on network TV. Tesfaye is just the 12th artist in history to score back-to-back Number Ones, a group that includes Elvis Presley, the Beatles and Taylor Swift. His new album, Beauty Behind the Madness, has sold more than half a million copies in a couple of months, and he’s preparing to launch a national arena tour in November. “I’m still digesting it, to be honest with you,” Tesfaye says of his success. “But the screams keep getting louder, dude.”

This scene would not have seemed possible in 2011, when the Weeknd appeared with a trio of cult-favorite mixtapes that established both his sonic template — drug-drenched, indie-rock-sampling, sex-dungeon R&B — and his mysterious, brooding persona. A press-shy Ethiopian kid from Toronto who has given only a handful of interviews, he has cultivated a near-mythical image as a bed-hopping, pill-popping, chart-topping cipher. “We live in an era when everything is so excessive, I think it’s refreshing for everybody to be like, ‘Who the fuck is this guy?'” Tesfaye says. “I think that’s why my career is going to be so long: Because I haven’t given people everything.”

Spend just five minutes with him, though, and he reveals himself: sweet, soft-spoken, surprisingly earnest. When I tell him he’s not what I expected, he nods. “When people meet me, they say that I’m really kind — contrary to a lot of my music.”

When talking about his art and his career, Tesfaye is blessed with a towering self-confidence and has no hesitation about declaring his own greatness. “People tell me I’m changing the culture,” he says. “I already can’t turn on the radio. I think I’m gonna drop one more album, one more powerful body of work, then take a little break — go to Tokyo or Ethiopia or some shit.” Hearing him boast about talking shop with Bono, or name-dropping “Naomi Campbell, who’s a good friend of mine now,” you may be tempted to see a diva in the making; or you may see a 25-year-old guy who’s stoked and incredulous to be in the position he’s in.

After rehearsal, Tesfaye is in the greenroom with his two managers, 31-year-old Amir “Cash” Esmailian and 35-year-old Tony Sal. Cash is a first-generation Iranian-Canadian sweetheart who occasionally yells things into the phone like, “You may as well bend me over a table, bro!”; Sal is a courtly charmer who grew up in Beirut during the Lebanese civil war and now dates a former Miss USA. Right now, they’re trying to figure out how to get from Norway, where Tesfaye will be for promo in a few days, to Texas, where he has a show. According to their tour manager, the only commercial flight from Oslo to Austin is at 8 a.m.

“What about noncommercial?” asks Cash. The tour manager says he’ll check, but they’re talking about hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Cash looks around and grins: “The label’s paying for it, right?”

I feel so much better today. I feel amazing right now.”

The next afternoon, Tesfaye is in a seventh-floor suite at his Soho hotel, having spent most of the previous 18 hours in bed. (There was also a B12 shot involved.) When a bellman brings in a silver tray with a selection of waters, Tesfaye pours himself a glass. “I just started being fancy, to be honest,” he says. “Like, I just started learning how to pronounce what I’m wearing.” He imitates a snooty shopgirl: “‘It’s not Bal-mane, it’s Bal-mahn.‘ ‘Oh, sorry!'”

When he first started recording as the Weeknd, Tesfaye was an unlikely star. “I was everything an R&B singer wasn’t,” he says. “I wasn’t in shape. I wasn’t a pretty boy. I was awkward as fuck. I didn’t like the way I looked in pictures — when I saw myself on a digital camera, I was like, ‘Eesh.‘” Instead of his face, his album art and videos featured black-and-white photos of artful nudes — a topless girl in a bathtub, a woman’s ass in a party dress. The aesthetic was American Apparel-style hipster catnip, right down to the Helvetica font.

Early Weeknd songs were atmospheric and chilly, their thick narcotic haze sliced by his broken-glass falsetto. The lyrics were an addiction counselor’s worst nightmare: pills, pain, shame, serotonin, danger. He and his crew posted three songs on YouTube and started spamming their friends on Facebook, then watched the play counts slowly climb. “I don’t know how many it actually was, but it felt like a million,” Tesfaye says. “Five hundred plays? Holy shit!” Toronto being a small town in some ways, the songs were heard by Drake’s manager, Oliver El-Khatib, who posted them to the OVO blog, where they promptly blew up. “Apparently, Drake wasn’t even fucking with it at first,” Tesfaye says today. “Oliver was the one vouching for me.”

The then-anonymous Tesfaye declined all interviews. In part, it was because he worried he wasn’t well-spoken enough: A high school dropout, he used to do crossword puzzles to improve his vocabulary, and to this day, he often wishes he were more articulate. “Me not finishing school — in my head, I still have this insecurity when I’m talking to someone educated,” he says. “I don’t want them looking at me like this fucking retard — no disrespect.” For months, no one even knew if the Weeknd was a person or a group. That’s when Tesfaye realized he “could run with the whole enigmatic thing,” he says now. “If it backfired, I probably would have been doing interviews. But people were kind of liking me being a fucking weirdo.”

“The Hills” is currently enjoying its fourth straight week at Number One, a feat made even more impressive because it took the place of another Weeknd track, “Can’t Feel My Face” — Spotify’s official song of the summer, and the only song about cocaine ever to be lip-synced by Tom Cruise on network TV. Tesfaye is just the 12th artist in history to score back-to-back Number Ones, a group that includes Elvis Presley, the Beatles and Taylor Swift. His new album, Beauty Behind the Madness, has sold more than half a million copies in a couple of months, and he’s preparing to launch a national arena tour in November. “I’m still digesting it, to be honest with you,” Tesfaye says of his success. “But the screams keep getting louder, dude.”

This scene would not have seemed possible in 2011, when the Weeknd appeared with a trio of cult-favorite mixtapes that established both his sonic template — drug-drenched, indie-rock-sampling, sex-dungeon R&B — and his mysterious, brooding persona. A press-shy Ethiopian kid from Toronto who has given only a handful of interviews, he has cultivated a near-mythical image as a bed-hopping, pill-popping, chart-topping cipher. “We live in an era when everything is so excessive, I think it’s refreshing for everybody to be like, ‘Who the fuck is this guy?'” Tesfaye says. “I think that’s why my career is going to be so long: Because I haven’t given people everything.”

Spend just five minutes with him, though, and he reveals himself: sweet, soft-spoken, surprisingly earnest. When I tell him he’s not what I expected, he nods. “When people meet me, they say that I’m really kind — contrary to a lot of my music.”

When talking about his art and his career, Tesfaye is blessed with a towering self-confidence and has no hesitation about declaring his own greatness. “People tell me I’m changing the culture,” he says. “I already can’t turn on the radio. I think I’m gonna drop one more album, one more powerful body of work, then take a little break — go to Tokyo or Ethiopia or some shit.” Hearing him boast about talking shop with Bono, or name-dropping “Naomi Campbell, who’s a good friend of mine now,” you may be tempted to see a diva in the making; or you may see a 25-year-old guy who’s stoked and incredulous to be in the position he’s in.

After rehearsal, Tesfaye is in the greenroom with his two managers, 31-year-old Amir “Cash” Esmailian and 35-year-old Tony Sal. Cash is a first-generation Iranian-Canadian sweetheart who occasionally yells things into the phone like, “You may as well bend me over a table, bro!”; Sal is a courtly charmer who grew up in Beirut during the Lebanese civil war and now dates a former Miss USA. Right now, they’re trying to figure out how to get from Norway, where Tesfaye will be for promo in a few days, to Texas, where he has a show. According to their tour manager, the only commercial flight from Oslo to Austin is at 8 a.m.

“What about noncommercial?” asks Cash. The tour manager says he’ll check, but they’re talking about hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Cash looks around and grins: “The label’s paying for it, right?”

I feel so much better today. I feel amazing right now.”

The next afternoon, Tesfaye is in a seventh-floor suite at his Soho hotel, having spent most of the previous 18 hours in bed. (There was also a B12 shot involved.) When a bellman brings in a silver tray with a selection of waters, Tesfaye pours himself a glass. “I just started being fancy, to be honest,” he says. “Like, I just started learning how to pronounce what I’m wearing.” He imitates a snooty shopgirl: “‘It’s not Bal-mane, it’s Bal-mahn.‘ ‘Oh, sorry!'”

When he first started recording as the Weeknd, Tesfaye was an unlikely star. “I was everything an R&B singer wasn’t,” he says. “I wasn’t in shape. I wasn’t a pretty boy. I was awkward as fuck. I didn’t like the way I looked in pictures — when I saw myself on a digital camera, I was like, ‘Eesh.‘” Instead of his face, his album art and videos featured black-and-white photos of artful nudes — a topless girl in a bathtub, a woman’s ass in a party dress. The aesthetic was American Apparel-style hipster catnip, right down to the Helvetica font.

Early Weeknd songs were atmospheric and chilly, their thick narcotic haze sliced by his broken-glass falsetto. The lyrics were an addiction counselor’s worst nightmare: pills, pain, shame, serotonin, danger. He and his crew posted three songs on YouTube and started spamming their friends on Facebook, then watched the play counts slowly climb. “I don’t know how many it actually was, but it felt like a million,” Tesfaye says. “Five hundred plays? Holy shit!” Toronto being a small town in some ways, the songs were heard by Drake’s manager, Oliver El-Khatib, who posted them to the OVO blog, where they promptly blew up. “Apparently, Drake wasn’t even fucking with it at first,” Tesfaye says today. “Oliver was the one vouching for me.”

The then-anonymous Tesfaye declined all interviews. In part, it was because he worried he wasn’t well-spoken enough: A high school dropout, he used to do crossword puzzles to improve his vocabulary, and to this day, he often wishes he were more articulate. “Me not finishing school — in my head, I still have this insecurity when I’m talking to someone educated,” he says. “I don’t want them looking at me like this fucking retard — no disrespect.” For months, no one even knew if the Weeknd was a person or a group. That’s when Tesfaye realized he “could run with the whole enigmatic thing,” he says now. “If it backfired, I probably would have been doing interviews. But people were kind of liking me being a fucking weirdo.”

Комментарии (0)

Минимальная длина комментария — 50 символов.